BACKGROUND

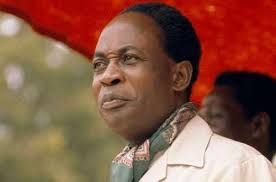

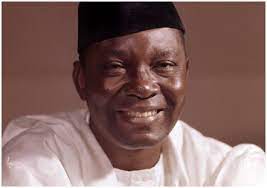

The concept of regional integration is not new; it has been intense since the 1960s when many African countries gained political independence from colonialism (Leshoele, 2020). In essence, there were two blocs that had diverse views on how to integrate Africa and the pace at which this was to be achieved. The first bloc was the Casablanca Bloc under the leadership of Dr. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, and the second was the Monrovia Bloc led by Nnamdi Azikiwe, the first President of Nigeria. The former argued for a wholesale and once-off comprehensive political and economic unification of Africa, from Cape Town to Cairo, the Horn of Africa to the West of Africa. The latter insisted that Nkrumah’s approach was not feasible; therefore, a gradualist and more cautious approach was necessary, first by forming regional economic communities, then an African Economic Community, with a politically integrated Africa emerging as the last step.

The Monrovia Bloc won the debate. The central focus of this concept is that almost all of these regional integration efforts and agreements (from the Lagos Plan of Action of 1980, the Abuja Treaty of 1991, the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) of 2015, and now the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) of 2018) are focused on trade and economic integration.

Between 2006 and 2016, three countries in Africa – Egypt, South Africa, and Morocco – accounted for 55.5 percent of Africa’s exports; and five countries – Nigeria, Angola, South Africa, Egypt, and Algeria – accounted for 55 percent of Africa’s imports (Ayoki, 2018). The implication is that conditions facing those countries will continue to influence the entire African continent’s service landscape.

Second, infrastructural constraints, including low rates of access to the Internet and poor connectivity, have hindered the participation of African economies in the most dynamic segment of the services trade, leading to high export concentration (in very few sectors such as transport, tourism, and travel-related services), heightening its vulnerability to external shocks.

Third, with less than 10 percent of the value of services produced in most countries entering into the economy’s export basket, growth in the services sector will continue to have a very limited influence on the world market share of global service exports. Reforms and programmes aimed at reducing trade barriers and the cost of trading across borders (raised by inefficient transport, border management, and logistics, poorly designed technical regulations and standards, licensing requirements and processes, among others) would not only create opportunities to directly expand service exports, but would also promote the development of competitive value chains of production across the region.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) rejects classical, neoclassical, and Marxist trade theories, appealing instead to non-aligned pan-Africanism (Obeng‐Odoom, 2020). It advocates continental free trade to overcome the lingering effects of slavery, colonialism, and neo-colonialism. Indeed, only true free trade can definitively decolonise global trade. To achieve its aspirations, AfCFTA and AU member countries will need to harness the power of diplomacy for intra-African and intercontinental trade, bearing in mind that good diplomatic relations within Africa and beyond promise to be a good step towards achieving the aspirations of the continent.

In diplomacy, a large volume of transactions between states goes through bilateral channels associated with traditional diplomacy (Akindele, 1976). Consequently, each African state has established a network of formal contacts with those members of the international community that it considers friendly and who similarly reciprocate this gesture of goodwill. Indeed, a noticeable worldwide trend in the last decade has been to diversify and increase such diplomatic contacts based on the increasing complexity and interdependence of the contemporary international system. However, bilateral relations between states, pervasive as they are, by no means constitute the totality of the channels of international transactions. Diplomacy has, over time, influenced trade and economic activities worldwide.

Increased globalisation has played a crucial role in shaping recent trends and concerns in the economic diplomacy of African states (Mudida, 2012). African states are increasingly interested in becoming relevant actors in the global economy. The economic diplomacy of African states is principally diplomacy of development targeted at enhancing the quality of life of the citizens of Africa. Economic diplomacy at bilateral and multilateral levels is helping to articulate the critical concerns of African states. This diplomacy in recent years has been defined by the engagement of African states with non-traditional allies such as China, India, and Brazil, and a strong impetus towards greater economic integration within Africa. The new economic growth of African states has spurred a much bigger middle class. The unearthing of new natural resources has helped create tremendous economic interest in Africa by Western and non-Western states that have engaged African governments to further their interests in economic diplomacy.

Within the ambits of the work of Mudida (2012), we believe diplomacy as a trade tool will harness continental resources toward achieving the goals of AfCFTA and those of other continents in furtherance of mutual benefits for Africa and the world.

An expanding trade relationship through diplomacy and other means appears to be the key to achieving the AfCFTA’s aspirations, and as such, a conference such as the Africa Diplomacy and Business Summit will no doubt strengthen the discourse on narrowing (and possibly eradicating) the barriers that prevent Africa from playing a leading role on the global trade stage.